Lexington one of the biggest swing areas in Trump vote results

Jed Kolko and /The New York Times

With most of the slow-to-report votes tallied, we finally have a clearer picture of last month’s presidential results. Despite the high polarization in the country that carried over to the reaction to the results — with 70 percent to 80 percent of Republicans still saying they disbelieve that Joe Biden won — in some respects the vote itself was less polarized than in 2016.

Compared with 2016, in 2020 there was less difference by race or ethnicity, and urban areas and suburban areas voted more alike. But the economic and education partisan divides widened. Mr. Biden gained in well-educated suburbs and exurbs, often in places that have tended to vote Republican in recent decades, like the Atlanta, Dallas and Phoenix areas.

In addition to these broad patterns, some specific shifts reflected local political loyalties.

As of Monday, reporting was complete enough to look closely at nearly all individual counties and metropolitan areas (which consist of one or more counties). Though some important patterns may show up only in more fine-grained precinct or individual survey data, counties make it easy to compare the entire country, over time, though many lenses.

These near-final county totals confirm a few patterns in the 2020 vote.

Stability

For all the ways that this election broke with precedent, the county-level vote pattern in 2020 was overwhelmingly similar to that in 2016. The correlation between counties’ vote margins for President Trump in 2016 and 2020 was 0.99. (A correlation of 1 represents a perfect relationship, and 0 represents no relationship.)

Strikingly, the vote was slightly less polarized than in 2016, breaking a pattern of increasing geographic polarization in the 2000s. The standard deviation measures how much an individual county’s vote typically deviated from the national average; this measure was a bit lower in 2020 after rising steadily from 2000 to 2016.

Furthermore, this year the vote in many counties was a small shift toward the center. The bigger that Mr. Trump’s victory was in 2016 in a given county, the more ground Mr. Biden picked up in 2020 relative to Hillary Clinton in 2016. In counties that voted for Mr. Trump in 2016, the 2020 margin shifted 3.2 percentage points toward Mr. Biden, versus a 1.9-point shift toward Mr. Biden in counties that voted for Mrs. Clinton in 2016.

Education

Among metropolitan areas with a population over 250,000, three Colorado metros — fast-growing Colorado Springs, Denver and Fort Collins — topped the list for swings against Mr. Trump in two-party vote share. Colorado has one of the nation’s highest rates of people with a four-year college degree, and this year it solidified its status as a blue state. Colorado’s shift against Mr. Trump was 8.6 points, second only to Vermont’s nine points.

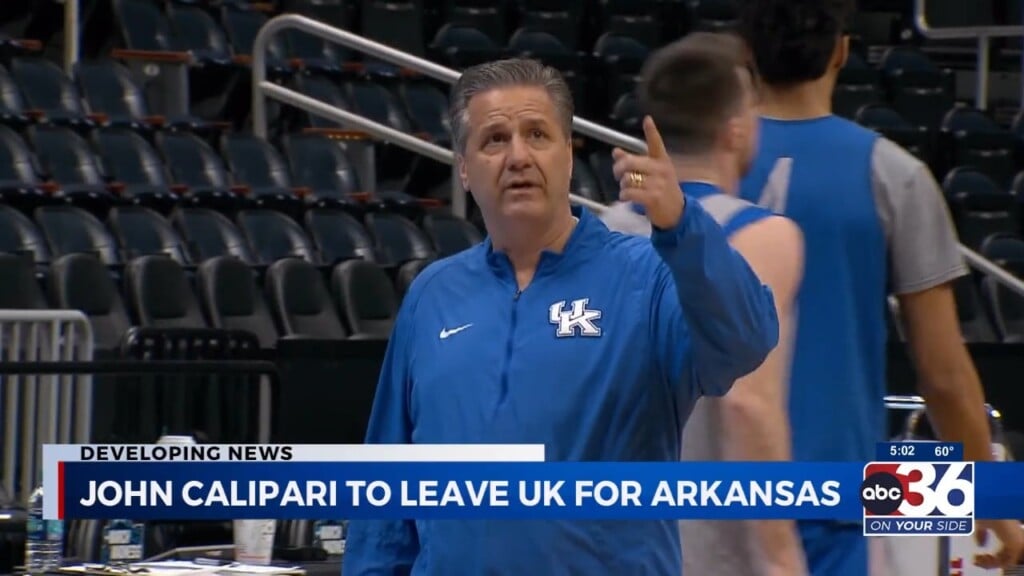

A part of conservative-leaning Kentucky posted one of the bigger anti-Trump shifts. The Lexington-Fayette, Ky., metropolitan area, which flipped from red to blue and is home to the University of Kentucky, has the highest percentage of college graduates in the region, and is in the top fifth of metros for college attainment.

And what about the big swing in the Huntsville area in deep-red Alabama? Fast-growing places with brighter economic prospects — correlated with a higher number of people with college degrees and more jobs in professional, tech and creative fields — moved toward Mr. Biden. A highly educated work force in Huntsville, first put to use in industries like aerospace, has become attractive to other businesses in recent years.

Suburban areas in Nebraska swung significantly toward Mr. Biden. Nebraska’s Second Congressional District, which includes well-educated Omaha, contributed one electoral vote to Mr. Biden’s tally. It “swung against Trump more than any swing state,” according to Dave Wasserman of the Cook Political Report. The swing was 8.8 points, as the district flipped from red to blue.

The Hispanic swing

Most metro areas swung Democratic, but the most extreme swings were toward Mr. Trump, and the biggest of those were in heavily Hispanic metros, like Miami and areas along the Texas border.

Initially it appeared that President Trump’s strength in 2020 relative to 2016 in heavily Hispanic counties might have been specific to South Florida and Texas border areas, despite the very different national origins and identities in those two regions. But data from later-reporting counties points to a national trend.

Leave a Reply